An excerpt from, Mighty Oak Warrior Programs founder, Chad Robichaux’s new book, An Unfair Advantage. Available on Amazon July 4th!

This was my first gunfight and I watched, in what felt like slow motion, as the slide of my Glock-22 functioned. To this day, I can picture the casings rolling out of the top ejection port. I could even hear the function of the weapons, like slow-motion factory presses stamping out parts on an assembly line. The rounds firing off were like firecrackers: there was no loud bang, no ringing ears. My awareness in that short moment was heightened to indescribable levels, but combined with an eerie sense of calm. I felt no anxiety.

Steve and I had reacted perfectly, firing twelve shots total, of which eleven impacted. This led to a later debate between the two of us as to who dropped the one round. (It wasn’t me, by the way.)

Russell, being hit center mass, did a half turn away from us and hit the ground on his knees. He looked back at me and our eyes met one more time. “You killed me,” he said. He knew it was the end.

I didn’t respond verbally. I just tackled him and ripped the rifle away, tossing it aside as I handcuffed him. His opposite arm that wasn’t holding the rifle must have been in front of his chest as he got hit, because the bones in wrist had been totally blown out by the .40 caliber hollow points. It felt like a limp noodle, and while the gunshot wounds to his body were not bleeding much, his arm was mangled and bleeding profusely.

As I patted him down for other weapons, I felt something slippery and noticed I was covered in blood from my hands to elbows. As I lay on top of Russell, I heard him exhale and then felt his life leave his body. It’s a feeling I will never forget.

I had dealt with death before, both of loved ones and friends.

When my brother was murdered, I was fourteen years old, and it really impacted me in a deep and painful way. But taking someone’s life for the first time gave me an immediate perspective of just how permanent death is.

I will never forget the way Russell’s wife screamed. Bystanders in the crowd held her back as she was fighting to get to me, or maybe to him, but she was hysterical and in great anguish. I also saw the children being held back by people in the crowd. Steve and I cleared the rest of the house, and other officers swarmed in to take control and assist. I looked around and saw a family’s home—the family pictures and toys, the table where they ate dinner together. I went into the kitchen sink and scrubbed my arms, washing Russell’s blood off of me; it seemed impossible to get it all off.

In the following weeks and months we faced media accusations. I stood before a grand jury who examined whether there should be a second-degree murder indictment, but Steve and I were cleared. Later, we were both awarded Louisiana’s highest law-enforcement medal for bravery: The Medal of Valor7.

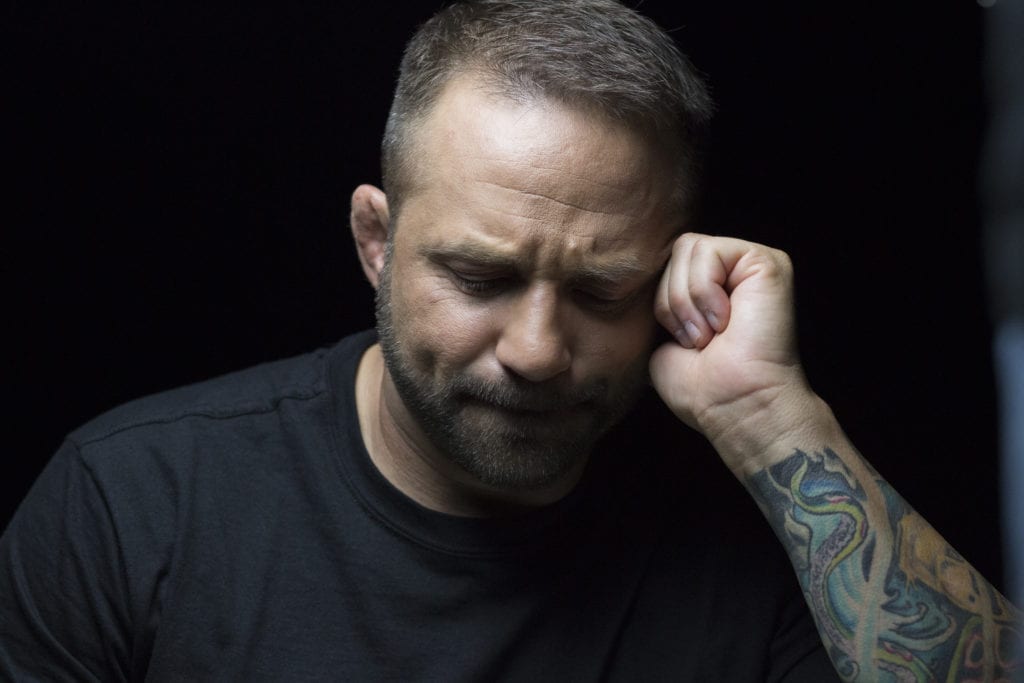

The ceremony was strange, and it was hard to be proud. I was thankful Steve and I were alive and that no innocent persons had been killed, but I was also angry with Russell for forcing me to kill him. I believe a piece of me died that night right along with Russell, perhaps not forever, but certainly for several years to follow. My struggles after this incident stemmed largely from my lack of maturity and understanding of what had happened, why it happened, and especially how I was supposed to deal with it.

On one hand, I was angry that Russell had made me kill him in front of his family; on the other hand, I didn’t feel badly about it.

Whether it was the accolades of my fellow officers, my joy of winning, or just the thrill of the event, as crazy as it sounds, I wanted to engage in and survive a hand-to-hand battle again. I actually began seeking out these types of altercations and pushed the envelope on every encounter with a bad guy. I wanted to provoke life-and-death circumstances to occur once more.

But at the same time, I began to question myself, thinking that because I didn’t feel badly and wanted to relive the moment something must be wrong with me—I must be an evil and murderous person. I began to judge and even fear myself. I couldn’t understand my feelings, but I was certain that I wasn’t going to share them with anyone. For years, I battled this alone in my mind, thinking I committed some “eternal sin” through my actions that night.

Years later, after Afghanistan, I found myself continuing to ask the same question of my motives and my heart. Had I become a monster? Today, I know the answer, and I know that I am a whole man again. I did my duty, loved my country, and am proud to have had the privilege to protect innocent human lives that were at stake. But learning the hard truths that helped me reach that conclusion wasn’t easy.

Now that I’m on the other side of my own struggles and working with other veterans and even police officers, I see clearly that I’m not alone in this inner battle of self-judgment and personal worth. Many warriors I speak with have the same thoughts I had—not with the survivor’s guilt, or “Poor me,” or “I’m so shaken up by all the killing, I’m seeing faces of dead bad guys in my sleep.” Rather, the questions that need to be worked through usually are:

- “Why don’t I feel bad about killing? I expected to feel bad but didn’t. Where was my empathy? Am I a monster?”

- “I’m evil. How can I be a good husband or father?”

- “Without a war, I have no purpose.

- “If my family knew what I have done, they would think badly of me”

These thoughts are common with guys who have been in the trenches and put lead down a two-way range. They are doing what they were trained to do.

Let’s not sugarcoat it. What is it that the Army and Marines train young infantrymen to do? Kill people and destroy things. Period. No need to make it sound pleasant. A young infantryman must be able to kill, and when he does, he can’t just pack it up and go home. He needs to wake up tomorrow and do it again. Why? Because war is ugly. It results in death to someone, and the infantryman knows, “It’s better him than me or my buddy.” It starts in day one of boot camp: the mental conditioning to prepare the warrior to pull that trigger, toss that grenade, or call in that fire support to take others’ lives away from them. Whether reluctantly or willingly, the question will always surface in the heart and soul of every warrior who has done such deeds: Was this just?

An answer to this question can be found in the many Bible stories where God…read more on July 4th when An Unfair Advantage is released on Amazon!

An Unfair Advantage

Take a journey with Force Recon Marine and Pro Mixed Martial Arts Champion Fighter, Chad Robichaux, as he shares a glimpse into the life of special operations, competition as a professional fighter, and deep insight into this world’s spiritual battles which we are all engaged. Chad shares personal stories of both success and failure experienced in Afghanistan, the MMA cage, and his biggest fight of all… coming home and facing a struggle with PTSD, a near divorce and almost becoming another veteran suicide statistic. Each chapter shares a parallel story of Biblical-time warriors who faced similar struggles and reveals An Unfair Advantage that led them to victory in the midst of those battles. Discover that same advantage for the battles you face and unlock the warrior spirit sewn in YOUR heart by God Himself.