by Bob Dees

I asked the packed church service in California “Are you a leader?” A few businessmen, city officials, and the pastor held up their hands. “I’m sorry, maybe some of you didn’t hear the question,” I responded. “Are you a leader?” The hands began to raise slowly until every person had signified “yes” to the question. They got the point: we are all leaders.

Posed with the same question, many of you may also initially think “No, I’m just a Mom… or a healthcare worker… or a student in high school… or a youth pastor in a church… or an elderly person in a rest home… or a teacher… or a homemaker… or one who is reaching out to the needy in your community… or put your name here __________ .” Whether you fall in one of the categories just mentioned, or in a more recognizable leadership position of businessman, statesman, or military leader; we are all leaders who influence others, for better or worse, with our every word and deed. As with David in Psalm 78:72, “So he (David) shepherded them (selfless service) according to the integrity of his heart (character) and guided them with his skillful hands (competence).” This is what God-honoring leadership for all of us looks like: Selfless service over time from a platform of character and competence.

During these days of COVID I have been asked numerous times about “leading through crisis.” In short, how do leaders from all walks of life navigate the complex COVID crisis we face, and inspire others to do the same? There are many aspects of this we could address – affirming those in the crucible, letting experts do their jobs, seeking historical parallels, shielding subordinates, mobilizing resources, and leading by example. These are addressed in great detail in Resilient Leaders. One other element of “leadership in extremis” seems to have resounded particularly during these days of COVID than all the others, however. Let me illustrate by way of a brief personal story:

Lieutenant Colonel Tom Kolditz was one of our artillery battalion commanders in the Second Infantry Division along the demilitarized zone (DMZ) in South Korea. He was awakened late in the evening on Halloween 1998 to learn that one of his armored vehicles had erratically swerved on a bridge, broken through the concrete siding, plunged 90 feet into the Imjin River close to the North Korean border, and come to rest under 30-40 feet of water with five of his soldiers trapped inside (who eventually drowned). This was definitely an unfolding crisis of tragic human proportion as well as one with significant political and military implications. He records the early moments of our encounter as he arrived at the scene of the accident:

As an artillery battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Tom Kolditz was awakened late in the evening on Halloween 1998 to learn that one of his armored vehicles had erratically swerved on a bridge, broken through the concrete siding, plunged 90 feet into the Imjin River close to the North Korean border, and come to rest under 30-40 feet of water with five of his soldiers trapped inside (who eventually drowned). This was definitely an unfolding crisis of tragic human proportion as well as one with significant political and military implications. He records the early moments as he arrived at the scene of the accident:

“As the helicopter flared to land near the bridge, I could see searchlights, medical evacuation helicopters, ambulances, soldiers moving about, and a few Koreans from a nearby village who were willing to leave their beds at 2:00 A.M. to witness the activity. As I walked across the bridge to the gaping hole in the concrete wall, I saw a camouflaged entourage of staff officers walking to the same place. Centered in the throng was the Second Infantry Division commander, Major General Bob Dees. He was responsible for more than seventeen thousand soldiers, five of whom had drawn their last breath. I saluted, and we exchanged the greeting of the Division: ‘Second to None, Sir.’ After rendering a report the information I had, I looked him in the eye, took a deep breath, and sighed. An accident of this magnitude would be on CNN in an hour, and five families would soon open their doors on Halloween eve, candy in hand, to find a casualty notification officer and an Army chaplain on their step. It was unquestionably the lowest point in my life thus far.

General Dees looked back at me and without hesitation said, ‘You know, Tom, it’s not whether bad things happen that makes or breaks a commander (leader). It’s what he does with the hand he’s dealt that really matters.’ His message was characteristic of a leader who had lost people in the past, and knew that more would be lost in the future. Leading is about respecting the dead and helping the organization grieve, not about how the leader feels. Death announces to good leaders that it is time to lead the living. Bob Dees is an in extremis leader.’”

(excerpted from In Extremis Leadership by Tom Kolditz, pages 138,139)

The simple principle I take from this vignette is “Honor the Fallen, Lead the Living.”

This tenet of navigating a crisis plays out at the leader level, and for each of us as individuals. The point of wisdom for a leader is finding balance between compassion for the fallen and leadership of the living – the typical “ditch on both sides of the road” metaphor. Certainly leaders observing the high death tolls and medical incapacitation resulting from COVID, as well as the toll taken on healthcare workers and first responders; do well to mourn the losses, honor the fallen, and encourage those that keep marching back into the fray at great personal risk. This compassionate aspect of leading in extremis also rightly includes a desire to protect the weak or vulnerable among us from the ravages of COVID.

Conversely, leaders of all stripes in this COVID crisis also need to focus intensely on “leading the living” through the crisis. Clearly part of this includes enabling healthy and enterprising citizens to prudently begin to restore productivity for themselves and fellow Americans. Some are doing this well and striking the right balance, yet some leaders are getting derailed by politics or by extreme risk aversion. The implications of this balancing act range from the national level, down to states and cities, and into every home in America. At each level, we must assess and balance risk, we must “Honor the Fallen, and Lead the Living.”

This principle is central to individual resilience as well. The reality is that most Americans have suffered loss during this pandemic – loss of jobs, loss of time, loss of opportunity, loss of a meaningful graduation event, loss of health, loss of loved ones, and for some even loss of hope itself. Most of us are trapped in the Resilience Life Cycle, somewhere still Weathering the Storm or in the early days of Bouncing Back. No doubt many of us have been “beaten down” in various ways, but gratefully in God’s strength and provision, we are “not destroyed.” (2 Corinthians 4:7-10).

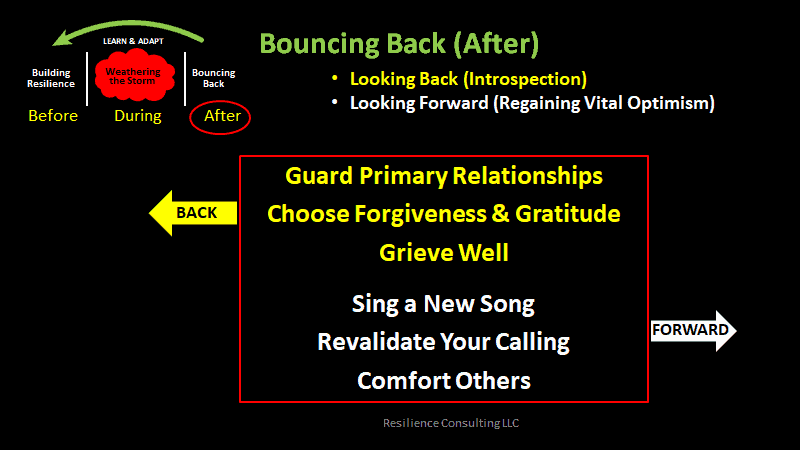

At risk of making anyone’s eyes glaze over, here is our Resilience God Style “map” for BOUNCING BACK:

While we have addressed many of these components individually — this is how they fit together. In BOUNCING BACK, one has to introspectively look back in the rear-view mirror, not trying to “stuff” the sense of loss or seeking to avoid the relational challenges and bitterness which often accompany loss. Then, one starts looking forward through the windshield; regaining vital optimism, a renewed sense of purpose, and the desire to comfort others. The “Honor the Fallen (look back on your loss), Lead the Living (move forward with hope and optimism)” principle applies here as well. May each of us respond in healthy God-honoring ways, achieving the right balance between looking back and looking forward, between grieving our losses and singing a new song, between Honoring the Fallen and Leading the Living. Gratefully, God the Healer is with us each step of the way, helping us “to the other side” of this COVID 19 storm, as well as the other many tribulations we face along life’s journey.

Without further comment, let us take a few moments to reflect on the soothing words of Psalm 23:

I shall not want.

2 He makes me lie down in green pastures;

He leads me beside quiet waters.

3 He restores my soul;

He guides me in the paths of righteousness

For His name’s sake.

4 Even though I walk through the valley of the shadow of death,

I fear no evil, for You are with me;

Your rod and Your staff, they comfort me.

5 You prepare a table before me in the presence of my enemies;

You have anointed my head with oil;

My cup overflows.

6 Surely goodness and lovingkindness will follow me all the days of my life,

And I will dwell in the house of the Lord forever.

Have a Blessed Week!

Respectfully in Christ,

Bob

Read more from Maj. General Robert Dees here: https://resiliencegodstyle.com/resilience-blog/